The evolutionary origins of the human butt

Look around in the animal kingdom. Not even gorillas, bonobos, or chimpanzees, our closest surviving relatives in the great ape family, have butts that are proportionately larger than ours. Our distinct style of locomotion is most likely the primary cause of this. We are the only extant mammals whose primary mode of locomotion is bipedalism. And turning into erect bipeds has had some significant consequences for our posteriors.

According to this article, the anatomic component commonly referred to as our “butt” is composed of fat, or adipose tissue, positioned over our gluteal muscles, which are attached to the bony pelvis. The shape of our butts is ultimately determined by the structure of our pelvis, a group of bones that has changed significantly over the previous six million years or so.

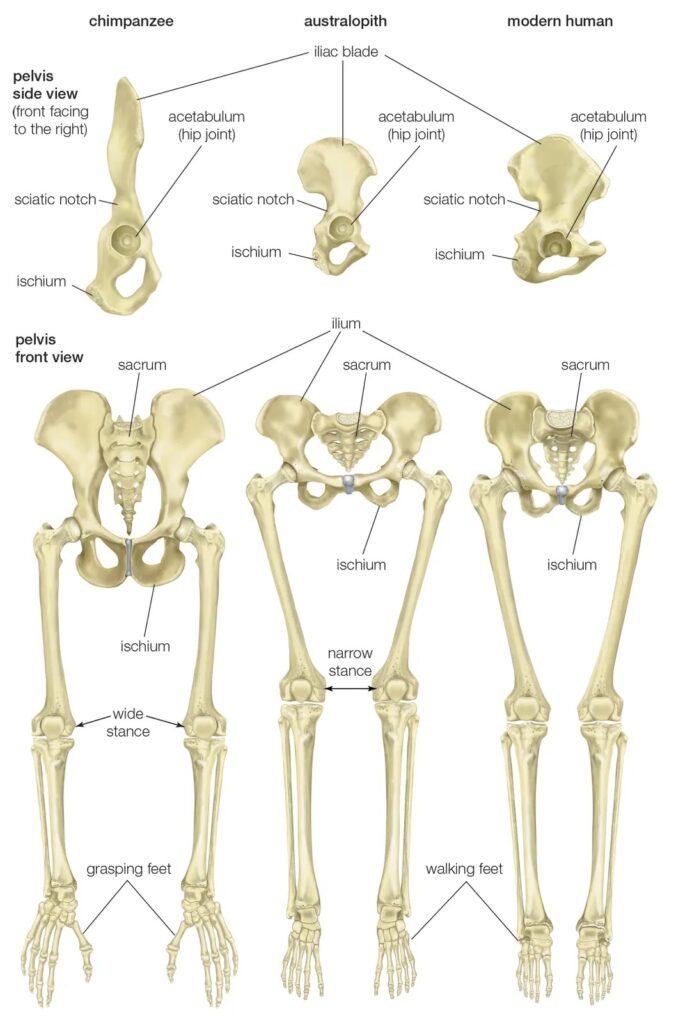

The sacrum, two innominates (sometimes known as “hip bones”), and one other comprise the pelvis. The ischium, pubis, and ilium are the three bones that comprise each innominate and fuse during growth and development. And the true factor that separates us from our ape relatives is the ilium.

The ilium of a chimpanzee has flat, rather tall, sides that face both forward and backward. Our pelvis is shaped like a bowl because our ilia are short and more curved to the sides. The evolution of bipedalism and the reorganization of our gluteal muscles, which enable upright walking, are linked to these changes in size and shape.

The gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus are the three gluteal muscles (the word “gluteus” means “butt” in Latin, thus that’s “biggest butt,” “medium butt,” and “smallest butt”). Compared to other primates, our gluteus maximus—especially the upper portion of it—is incredibly large. It gives us strength when we run or climb stairs, and it extends and retracts the thigh. And that’s what largely determines the shape of our behind. Nonetheless, in other apes, the gluteus maximus need not be a key participant because the so-called “lesser gluteals” (gluteus medius and minimus) perform much of this function.

Instead, when we stand on one leg—as we do every time we take a step forward—our smaller gluteals are keeping our hips from falling to the side. Their ability to do so is made possible by the ilia’s curved shape, which modifies the location and function of those muscles. Rather than power, our smaller gluteals provide stability.

From the 4.4 million-year-old early human relative Ardipithecus ramidus (possibly—this fossil’s pelvis was in pretty bad shape when it was discovered), to australopithecines like Lucy, and finally to Homo erectus, we can trace this change in ilium shape and inferred gluteal function throughout our evolutionary history. Throughout time, the ilium has typically grown shorter, wider, and more curved, meaning that our butt has undergone a multi-million-year transformation to become the anatomical feature that it is today.

The fat on our bums is the final characteristic that makes them special, and it may also play a role in our evolution into bipeds. The brains of humans are comparatively large and energy-intensive. For a non-aquatic mammal, our bodies store energy as fat, and we have a comparatively high amount of it. Anthropologists have concluded from this that body fat protects our metabolically costly brains from periods of famine.

We seem to be able to accomplish this because moving about on the ground while walking is an energetically efficient activity. It also avoids the drawbacks of living among trees, which would take a lot of energy to sustain our entire weight on tree branches and be dependent on gravity. Given their strength, flexibility, and limb proportions—not to mention their opposable large toes—orangutans do fairly well at this.

All of these improvements sound amazing, but there is one significant drawback to having human-like amounts of muscle and fat on our posteriors: we poop more messily than most other primates. Imagine a quadruped, such as a chimp, with its legs and trunk meeting at an angle, with its anus facing more outward and the butt at the corner. Furthermore, the aperture isn’t confined between the big buttcheeks. For us, there is only a straight line—no angle. We increased the padding around the anus and rotated it to point more downward by standing up. Hence, a messier defecation thanks to evolution.