They cost 1 penny and were called Monkey Closets

The Great Exhibition of 1851, an international exhibition that took place in Hyde Park, London, from 1st May to 15 October 1851, presented the first paid toilet with 827,280 visitors paying a 1-penny fee to use them.

The exhibition was also known as The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held) presenting elements of culture and industry that became popular in the 19th century.

At the Exhibition, George Jennings, a Brighton plumber, was the one who installed the so-called Monkey Closets in the Retiring Rooms of The Crystal Palace. These public toilets caused great excitement as they were the first public toilets anyone had ever seen. For ‘spending a penny’, they received a clean seat, a towel, a comb, and a shoeshine. That’s where the euphemism ‘to spend a penny’ comes from.

The toilets were scheduled to be closed when the show ended and the Crystal Palace was relocated to Sydenham. But Jennings was able to persuade the organizers to keep them open. They agreed, and the penny toilets eventually brought in almost £1000 per year.

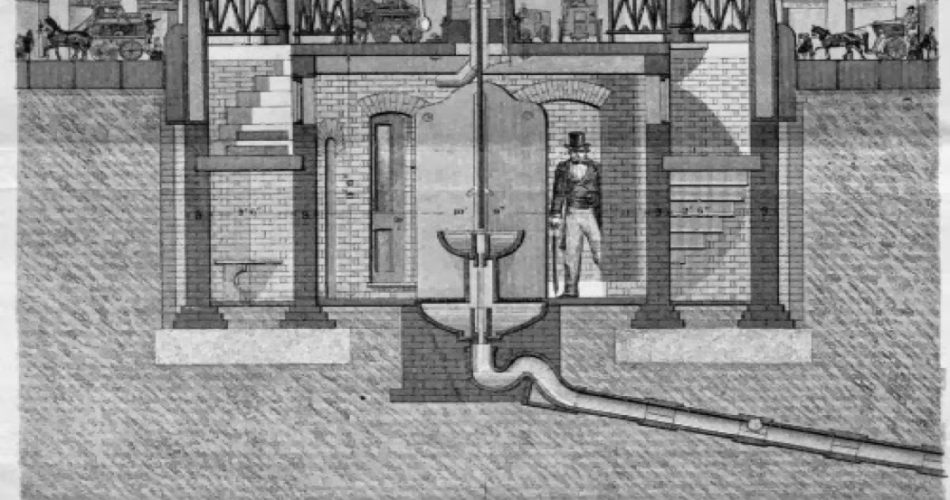

Following the success of Jennings’ Crystal Palace lavatories, public toilets began to appear in the streets, with the first one opening on the 2nd February 1852 at 95, Fleet Street, London, next to the Society of Arts, and another for women opening a few days later at 51 Bedford Street, Strand, London. These ‘Public Waiting Rooms’ had water closets in wooden surrounds. The entrance cost was 2 pence, with additional charges for washing or clothing brushing. These new facilities were advertised in The Times as well as on handbills distributed across the city. However, due to unpopularity and the cumbersome design of the lavatory and flushing process, these ‘Public Waiting Rooms’ did not become successful and were finally abandoned.

Sir Henry Cole (one of the Great Exhibition’s main promoters and inventor of the commercial Christmas card) and Sir Samuel Morton Peto (a building contractor who had erected Nelson’s Column and built the Reform Club, Lyceum Theatre, and a few other London buildings) thought the scheme would be extremely profitable, this wasn’t the case. Mr. Thomas Crapper enhanced Jennings’ original flushing mechanism, which promised a better flush with every pull, and these improvements contributed to the public toilet’s growing popularity.

Crapper also invented the ballcock, which is an important toilet innovation but although he is commonly credited with creating the flush toilet, this is incorrect.

Regarding George Jennings, died in a traffic accident on April 17, 1882, when his horse shied and hurled him across the road into a dust cart. Then he was taken to the hospital with minor bruises and a broken collarbone. Later, he appeared to be doing well until he developed lung congestion and died at the age of 72 y.o.

His company continued its work but was led by his son, and by 1895, it had already installed public toilets in 36 British towns, as well as Paris, Florence, Berlin, Madrid, and Sydney, not to mention remote places in South America and the Far East, thanks to a new improved way of flushing. And so it was that Victorian designers, architects, and engineers created public restrooms to a very high standard.

Then, when above-ground toilets were required, they were designed to be visually attractive, using high-quality materials like marble and copper, and supplied with excellent ceramics and tiles.

In London, authentic Victorian public toilets may be identified by the beautiful and elaborate railing work above ground, with steps leading under street level.

Source thevictorianist.blogspot.com